What everyone gets wrong about the problem

An argument as old as the internet itself, and probably even older that spread by word of mouth. The question at the center of the argument is this: “If an airplane is on a treadmill that is moving backwards as fast as the plane is moving forwards, can the airplane take off?”

As with many mind teasers and thought experiments, it’s important that (1) the question being asked addresses a specific problem, and (2) reasonable assumptions are made. The reason there is so much argument concerning the airplane on a treadmill is that the question fails on point 1; the question is broad, and leaves many people confused as to what’s being asked.

XKCD does a fantastic breakdown of the arguments surrounding this question, but here we’ll try to simplify WHY people get confused, why that confusion is a reasonable (not an idiotic) response, and how the question should have been asked so anyone would have known that yes, the airplane can take off on a treadmill.

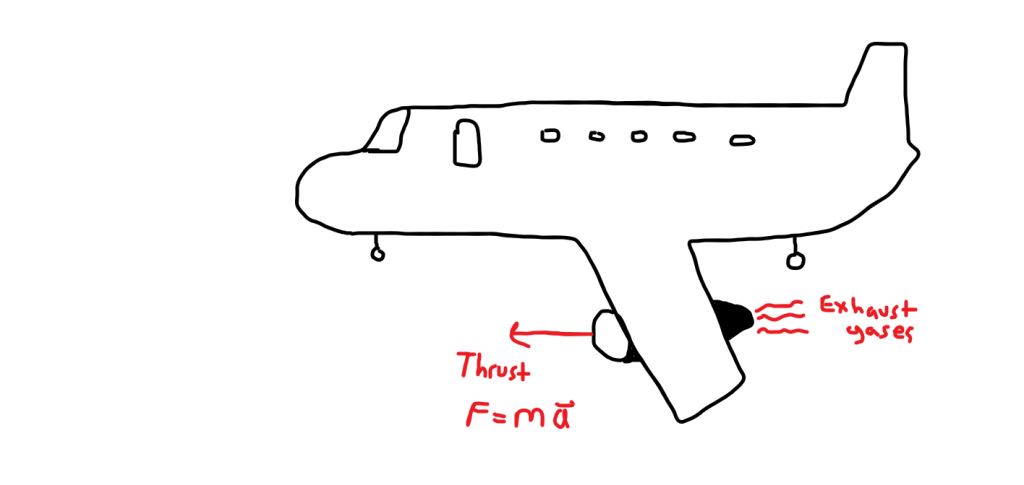

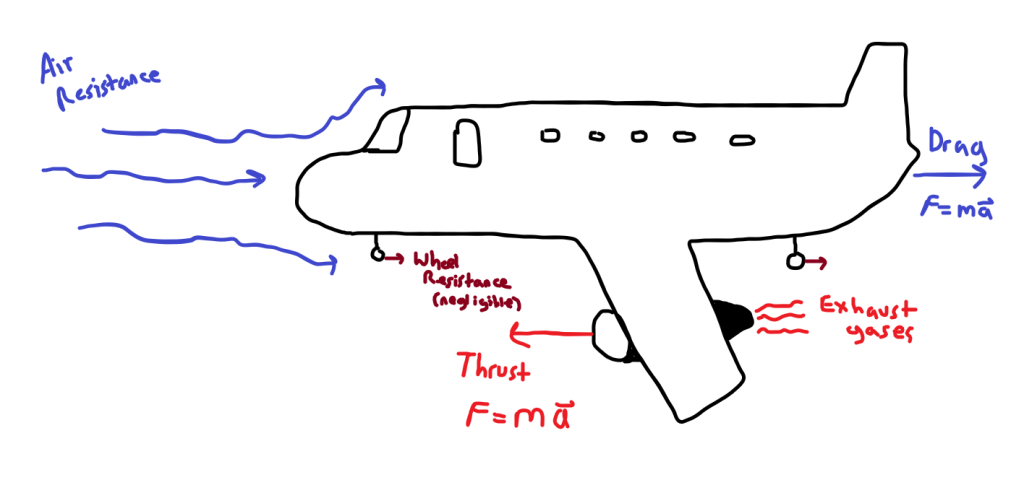

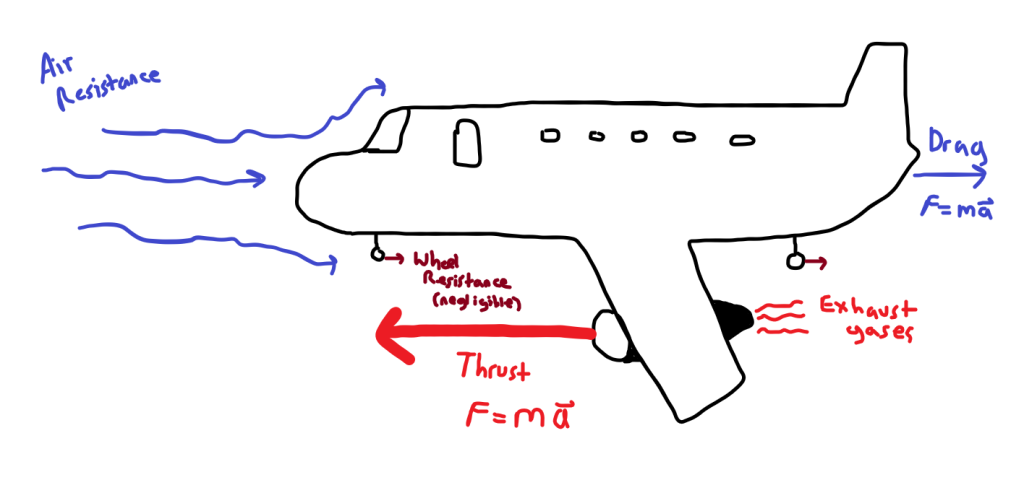

Let’s talk about how an airplane flies first. An airplane generates forward motion by creating thrust through use of a propeller(s) or a jet engine(s) (a “jet” is shown above). The wheels are typically not powered, and are “free rolling”; that is, the wheels will spin as fast backwards or forwards as required by the airplanes speed on the ground. The wheels are also designed to provide as little internal friction (resistance to rolling) as possible, so as to make takeoff easier (when a plane lands, brakes are applied to the wheels to provide the resistance to stop the plane). This means that during takeoff, the only significant forward force on the plane is the thrust of the engines.

Thrust is a force, which is created by accelerating a mass (in this case, air and fuel combustion products or gases). A jet engine creates thrust by combusting a fuel-air mixture, causing the air and exhaust gases to become more energetic and accelerate. During takeoff, the jet engine has a fan at the front that “draws” air in to provide the inflow. During steady flight (in-air), the flow of the incoming air as the plane travels through the sky is sufficient, even though the fan still spins and provides some additional positive pressure to the engine, making combustion more efficient. Think of the exhaust of the engine flying back to be “pushing” the plane forward.

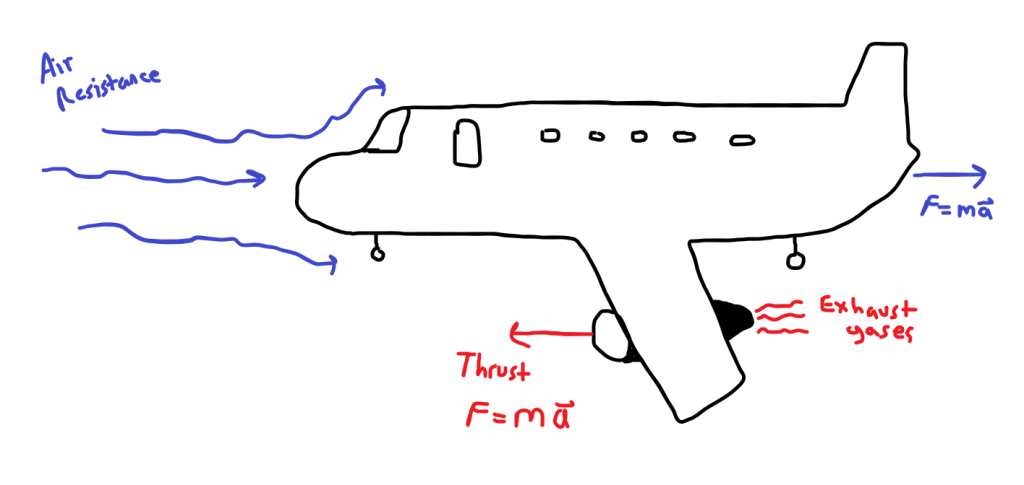

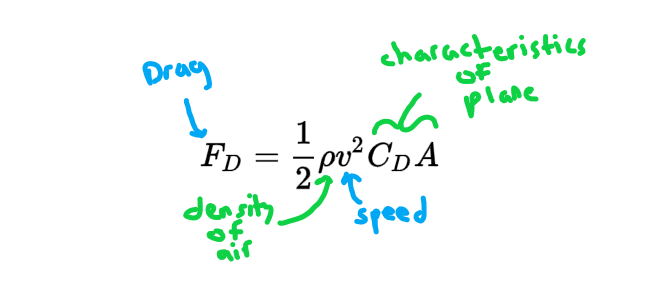

However, the forward force of thrust is not the only significant force on the plane in the horizontal direction. As the plane moves forward, it encounters air molecules that are typically moving slower than the plane (a tailwind actually causes the air to be moving faster than the plane until plane is traveling faster than the wind). These air molecules, while small, begin to create “drag” on the plane, or air resistance, as each air molecule displaced by the plane moving forward has to be pushed out of the way. Additionally, some of these air molecules then “stick” to the plane and flow over it, causing friction (see the blue arrows moving up and under the plane; this is also happening on the sides). The combination of these effects creates drag, or air resistance. As the plane moves faster, the drag, or air resistance, increases by the formula:

In the formula above, the green arrows note terms that are out of our control once the plane is built and once we’ve chosen where we’re going to fly. The “CD” and “A” terms represent the drag coefficient and the cross-sectional area of the plane moving through the air, respectively. These cannot be significantly altered once the plane is designed and built (although some hull treatments or replacing loose/inefficient parts of the plane can lower these factors). The “p” represents the density of the air, which is entirely out of our control as it depends on the environment totally. As you can see though, lower density air would decrease the “p” term, causing the force of drag to decrease (although the density of the air plays an important factor in lift, which we’ll get to).

Since we can’t do much about the green, let’s focus on the terms shown by the blue arrows. The force of drag is then mostly determined by the velocity, or speed, of the plane. In fact, this term is squared; meaning that as speed increase, the force of drag will increase faster relative to the increase in speed.

Knowing this and assuming that the wheels are essentially frictionless (and therefore a nonexistent or negligible force in the horizontal direction), the only forces acting on the plane moving forwards or backwards is thrust and drag.

We now can see that the only thing that causes the plane to move forwards or backwards then is thrust and drag. The wheels (assuming someone didn’t leave the brakes on) will spin as fast as necessary (in either direction) to maintain where the plane was going to begin with: if the plane is providing sufficient thrust to overcome any drag (and remember, without a headwind, drag is zero if the plane is stationary), the plane will move forward, and the wheels will spin as fast as necessary to accommodate the plane’s motion.

So why does the treadmill trip everyone up? It all comes down to how the question is phrased, and assumptions about the wheels. If we assume the wheels are frictionless (ideal scenario, but not realistic) or pretty much close to it when compared to the thrust and drag forces (realistic; there’s always some internal friction in a real-world wheel), then we know that no matter how fast the treadmill moves back, the wheels will just spin faster to maintain the plane’s position (if stationary) or motion (if moving). However, the question does not address what’s going on with the wheels. For example, if we picked a situation where the brakes were left on inadvertently, and the sizing of the engine’s thrust is not sufficient to overcome the force of friction applied to the wheels (or only enough to allow them to roll slowly to match the treadmill’s speed), then yes, the plane would not move forward and no air would flow over the wings to provide lift (preventing takeoff). This could also be true if we picked the world’s worst wheels, kind of like putting the proverbial caveman’s wheels on the plane; the force of internal friction could be enough to prevent the plane from moving forward relative to the treadmill. Below is the graphic of the plane with the forces represented proportionally to what’s happening during takeoff; thrust is the dominant force, while drag is minimal (since planes are designed to not have excessive drag) and wheel resistance is negligible:

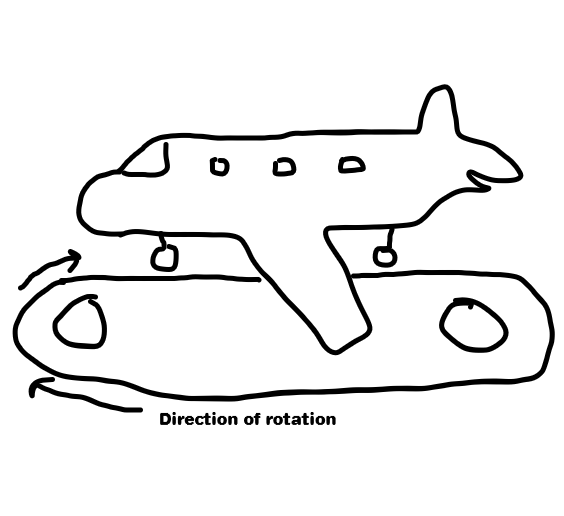

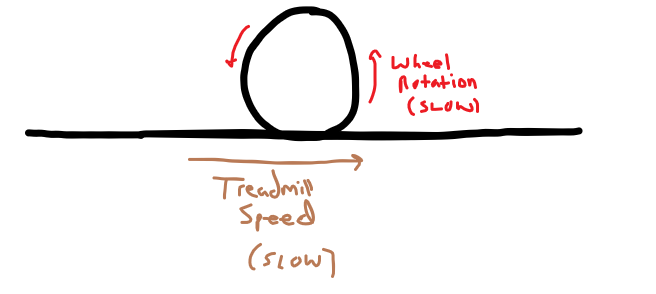

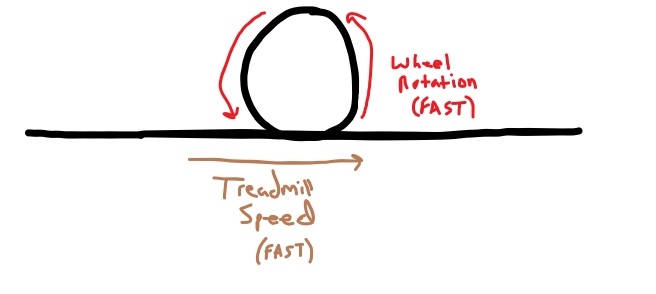

And here are two graphics showing what happens to the wheels at varying treadmill speeds:

As shown above, if the treadmill is moving slowly, the wheels rotate slowly to match the plane’s position or motion. If the treadmill is sped up, like in the second image, the wheels rotate faster to maintain the plane’s position or motion. The takeaway is that the speed of the treadmill (in ideal and realistic scenarios) does not affect the position or motion of the plane since the wheel’s will spin faster or slower to accommodate the difference in relative speed between the treadmill’s surface and the plane’s motion.

It’s important to note that in a realistic scenario, starting a treadmill while the plane is stationary and engines are off would probably cause the plane to start moving backwards, especially if the treadmill is started slowly. For the wheels to roll, there has to be some initial force to overcome the small amount of the wheel’s internal friction, and if the wheel’s do not roll, then yes, the plane will sit on the treadmill with the wheel’s motionless and travel backwards; this is immediately resolved once thrust is applied.

So in conclusion, why is it reasonable to think that the plane couldn’t take off on a treadmill? Again, the problem statement does not mention anything about the wheels, the magnitude of their internal friction, or if the wheels are “locked” at a certain speed. For example, if the treadmill were moving as fast as the wheels would during a normal takeoff, and the wheels were “locked” or somehow limited to that speed, then the plane could not takeoff (unless sufficient thrust were applied to break the rolling friction and cause the wheels to start skidding down the runway as the plane accelerated forward). However, if the problem statement were reasonable, it would state “Is it possible for a plane to takeoff on a treadmill moving as fast as the plane, if no brakes are applied and the internal resistance to rolling of the wheels is negligible?”. If the problem is stated so, then it is likely most people (including me) would not immediately assume that the plane could not take off.

Hopefully you enjoyed this simplified explanation, please let me know if you’d like to see other content!