How to win big if given the choice to change your pick

In the classic television game show Let’s Make a Deal, hosted by Monty Hall, contestants occasionally participated in the following game:

Three doors are presented to the contestant. Behind one of the doors is a prize, while behind the other two doors is no prize (or often, a goat or other animal representing no prize). The contestant is allowed to pick one door; after their pick, one of the doors containing no prize is opened, and the contestant is then given the option to maintain their choice or pick the other, remaining door.

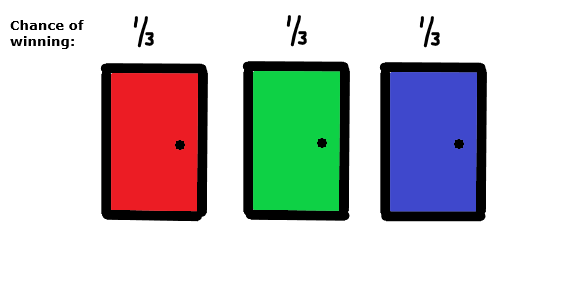

The above represents the three doors (red, green, and blue). On the show, contestants often maintained their original choice, which sometimes led to a prize being awarded (they’d picked the door with a prize initially) but often led to no prize being awarded (the door they’d picked was one of the two “no prize” doors).

In short, the contestants were playing a weak hand (to make a poker reference) by maintaining their choice. In 1975, the statistician Steve Selvin posed and solved the problem in a letter to American Statistician, dubbing it the “Monty Hall Problem”. While many people insist that it shouldn’t matter, we’ll look at why changing your original choice makes sense if you want to maximize your chances to win a prize.

Initially, the contestant has a 1/3 chance (33.3%) of selecting the correct door. These are pretty slim odds. In fact, since 2 out of the 3 doors have no prize, they actually have a 2/3 chance (66.6%) of selecting the wrong door. Let’s pretend the blue door contains the prize.

As you can see, out of the 3 choices, the contestant is more likely to select the wrong door than the correct door if chosen at random; and since the prize door is set randomly and the contestant has no other information upon which to make their choice, they are essentially choosing at random with a 2/3 chance of getting it wrong.

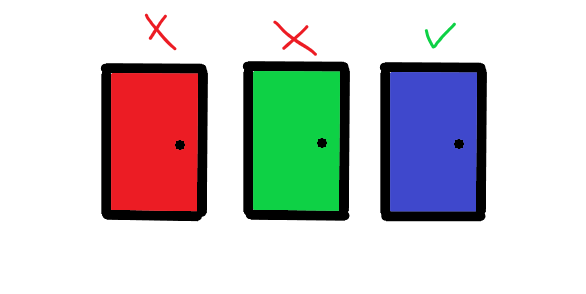

So let’s say the contestant picks the red door (maybe it’s their favorite color). Once the selection has been made, the host will open the other wrong door (the green door) revealing no prize.

At this point, the contestant has to make a choice: stick with the red door, or switch to the blue door. In this example, we already know that switching to the blue door would be correct (but the contestant doesn’t know that). So how what math would convince the contestant that switching to the blue door is the correct choice?

At the beginning, we figured out that the contestant only had a 1/3 chance of picking the correct door at the start. Nothing has changed about that initial pick; there’s still only a 1/3 chance that the red door is correct. However, the prize has to be behind one of the doors, and we know it’s not behind the green door now. And as it happens, all probabilities have to add up to 1 (if working in fractions/decimals) or 100% (if working in percentages). So where has the rest of the probability gone?

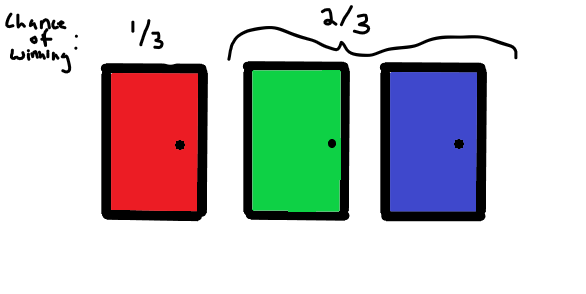

If the red door only has 1/3 chance of being correct, and we know the green door is eliminated, then it stands to reason that the blue door must have a 2/3 chance of having the prize. This may not sound true, but let’s look at the setup again:

Based on the initial door pick only having a 1/3 chance of winning, their must be a 2/3 chance of the prize being behind the other two doors. In other words, if they could pick the blue and the green door together vs. the red door, they would have a 2/3 chance of winning vice a 1/3 chance of winning (twice as likely to win the prize).

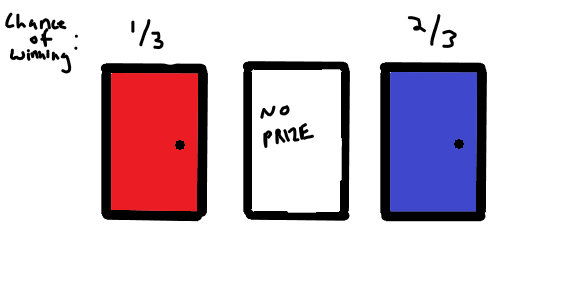

Therefore, once the green door is eliminated, the remaining 2/3 chance rests with the blue door:

This is true regardless of the initial door picked; without knowing anything else, switching your pick from the initial door after the reveal of one of the no prize doors doubles your chances of winning from 1/3 to 2/3.

This logic rests entirely on the premise of the game, and the fact that we gain information about the doors as the game progresses (one of the no prize doors is opened). For example, if there was no reveal, the chances would still be 1/3 for each door, and switching doors would have no effect on your chance of winning. However, in this game, switching your initial pick makes it twice as likely you’ll win the prize.

One final note: switching doors does not guarantee a win, only a 2/3 chance of winning (still a 1/3 chance you’ll lose). The red door could just as easily have been the prize door in the above examples (although only a 33% chance of that, vice a 66% chance it was the blue door).

I hope you found this interesting, helpful, or enlightening. Please let me know if you’d like to see any specific content via my email, nate@thepracticalstudent.com.